Would you put a chip in your brain to find true love? This either romantic or dystopian question is the premise of Netflix’s French sci-fi thriller Osmosis.

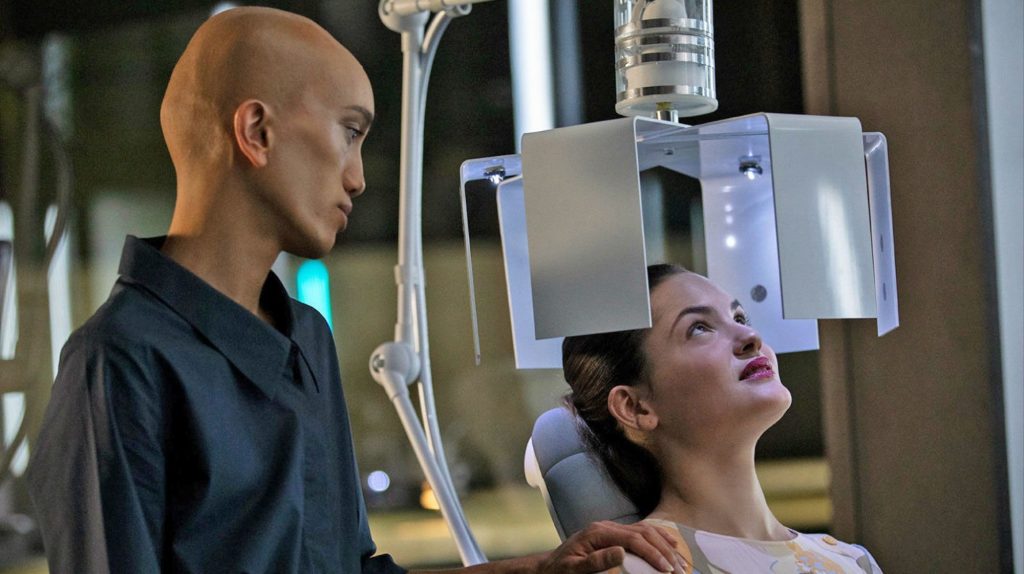

The show is set in the eponymous tech company who are about to launch a product that does exactly this: implants a chip in your brain that will guide you to your soulmate. An AI called Martin uses sophisticated data processes to find the person who is the perfect match for you.

However, the trial of Osmosis doesn’t go entirely to plan. Partly because Osmosis’s creator, Esther Vanhove, plans to use the brainwaves of the initial test subjects to further her own research. What follows is a dark thriller about desire, the difficult road to finding a healthy relationship and the lengths people will go to save the ones they love.

Data knows you better than you know yourself

The show highlights a contemporary fear: that AIs and big data know us better than we know ourselves. In Osmosis, Ana, who is unsporty, discovers that her soulmate is a fitness instructor, whilst Lucas, a man in a relationship, discovers that his ex-lover is his real soulmate.

The AI, Martin, understands Osmosis’s users better than they do. Through the data it gathers, it sees truths about the subjects they are unable or unwilling to see about themselves. We think of ourselves as individuals, containing our own private universe, and that no one can understand this private universe better than we can. The idea that a machine can understand us better than we know ourselves is a fundamental challenge to our belief that we are unique individuals.

If we are not unique people with an internal universe known only to ourselves, if data reveals truths about ourselves that we cannot see, and if machines can make better decisions for us than we can (from choosing what to watch to choosing our romantic partner) then how can we make decisions ourselves? Do we even have free will if we are better understood as a piece of data that is part of a larger set?

Coupled with it is the scary idea that all this technological beneficence, created to help us find the perfect romantic partner or the perfect take away, could actually be manipulating us. If the machines know us better than we know ourselves, they can use this to subtly influence our decisions in a way that we might not be aware of.

If a machine can use data to see our deepest desires, even the ones we keep secret from ourselves, then they – or the people who control them – can use this information against us.

Manipulation

In Osmosis, Esther has edited the data to help her research, which affects the experience of the users. They are being manipulated without their knowledge or consent. The working of Osmosis is obscured from its users. It’s a black box, like many tech platforms that we use. In both our world and the world of Osmosis, the users of tech platforms don’t know if they are being manipulated or how their information is being used.

This reflects several contemporary fears about big tech companies and their use of our personal information, from AI research to the role that Cambridge Analytica played in the 2016 US presidential election. We cannot escape the fear that big tech companies are using their ability to understand us better than we know ourselves to subtly manipulate our decisions.

Cambridge Analytica is a good example of how data and tech platforms can be used to influence people’s behaviour. Donald Trump’s presidential campaign didn’t use many of the online ads that they bought, which were targeted using data and research provided by Cambridge Analytica, to directly urge voters to cast a vote for Trump. That would have been too obvious and easily exposed.

Instead, they used these online ads to increase swing voters’ anxiety on topics such as gun rights, which made these issues more important to voters when deciding who to vote for. By making voters value issues that Republicans are seen as strong on, they were able to turn out more voters for Trump. Republicans want voters anxious about abortion. Democrats want them anxious about health care. The voters weren’t aware that they were being influenced.

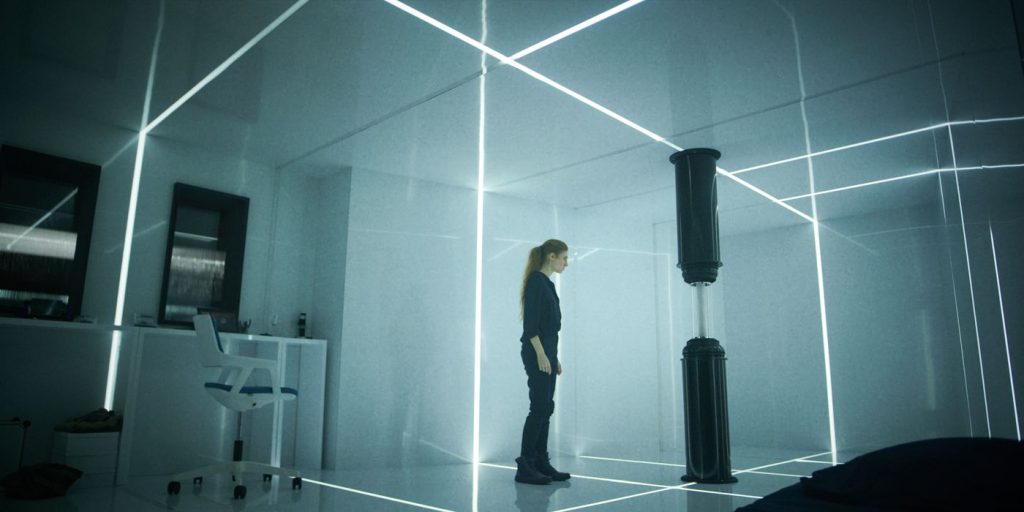

Devs

There are other shows that explore this fear. A recent example is Devs, where a mysterious tech company is using algorithms and data to build a model that can predict the future. As a sci-fi plot, it’s not that far-fetched when you consider the grandiose ways that many tech companies talk about their ambitions.

Like Osmosis, Devs speaks to our fears that humans are predictable and easily manipulated. These shows are part of a movement or subgenre of tech-sceptical science fiction that includes shows such as Black Mirror. These shows are pushing back against the technological utopian rhetoric of Silicon Valley and past depictions of future technology in science fiction that were overly optimistic, from Star Trek to I, Robot (the book, not the awful film).

As well as highlighting our fears about the role of technology in our lives, Osmosis also explores a problem with a technological utopian outlook. Osmosis as a system can use data to create perfect romantic matches, but it can’t fix human problems. Just knowing who you are most compatible with doesn’t instantly make you happy or create a fulfilling relationship. The character’s personal problems or secrets get in the way of their happiness, such as Lucas who is already in a relationship with someone else when he discovers who his match is.

Even if you do find a partner that you can be happy with, this doesn’t fix all your problems. This is true for Niels who is a sex addict and has poor impluse control. Even finding love doesn’t fix his addiction. This is true of Esther’s brother, Paul, who has found love through Osmosis, but still has relationship troubles with his partner.

In our world, technological fixes to social problems come up against human barriers. Technology can connect people better, but it also creates filter bubbles that facilitate the spread of disinformation. Social media allows you to connect with people who share your interests, however niche that is, but this is also true for Nazis and has thus facilitated the global coordination of a new far-right movement. The human element is often overlooked in the designing of new technologies.

Technological scepticism within science fiction

The show Osmosis highlights the Faustian bargain that many feel we are making by letting technology run our lives: it delivers utility for us but we stand the risk of losing our humanity. Total connectivity has created strife in our society as well as brought us closer to our loved ones. Now we are also worried that the technology we use is manipulating us in subtle ways that we may not be aware of.

Despite the incredible ability of modern technology, it cannot solve the problems of our human flaws, and in some cases the technology exacerbates these flaws. Osmosis as a show is more optimistic than Black Mirror, but fits part of a wider trend of technological scepticism within science fiction.